Notes on Probability

Contents

(probability=)

Notes on Probability#

This document summarizes key concepts in probability theory. It is intended to be a concise reference for what we will be using, not a thorough tutorial exposition.

The concepts in this note are introduced in Week 4.

Set Concepts and Notation#

A set

If

Kinds of Sets#

There are, broadly speaking, three kinds of sets in terms of their cardinality:

Finite sets have a finite number of elements. There is some natural number

Countable sets (or countably infinite sets) are infinite sets with the same cardinality as the set of natural numbers (

Uncountable sets are infinite sets whose cardinality is larger than that of the natural numbers. The real numbers (

We also talk about discrete and continuous sets:

A continuous set

A discrete set is a set that is not continuous: there are irreducible gaps between elements.

All finite sets are discrete. The natural numbers and integers are also discrete. The real numbers are continuous. Rationals and algebraics are also continuous, but we won’t be using them directly in this class.

Note

While

Events#

A random process (or a process modeled as random) produces distinct individual outcomes, called elementary events.

We use

Probability is defined over events.

An event

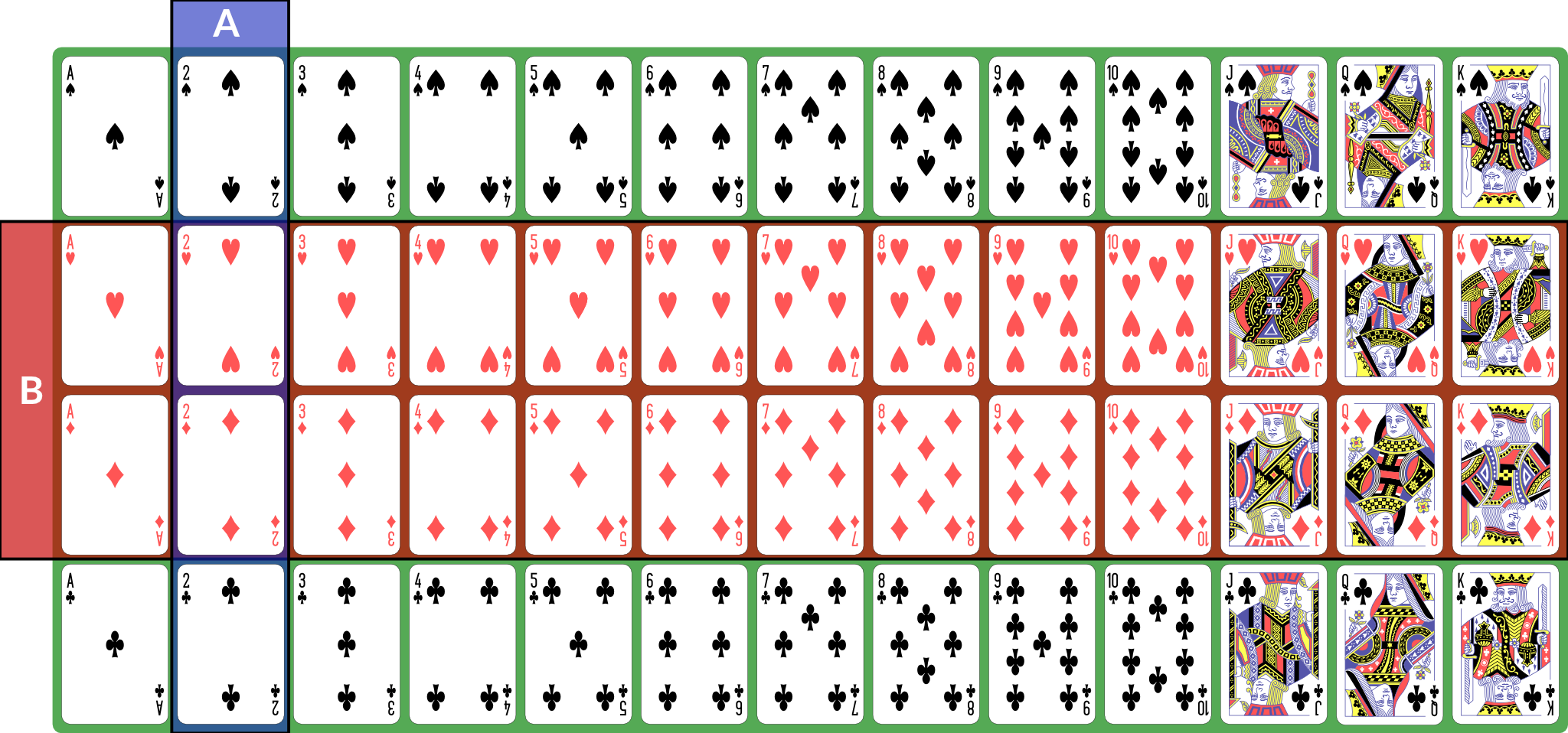

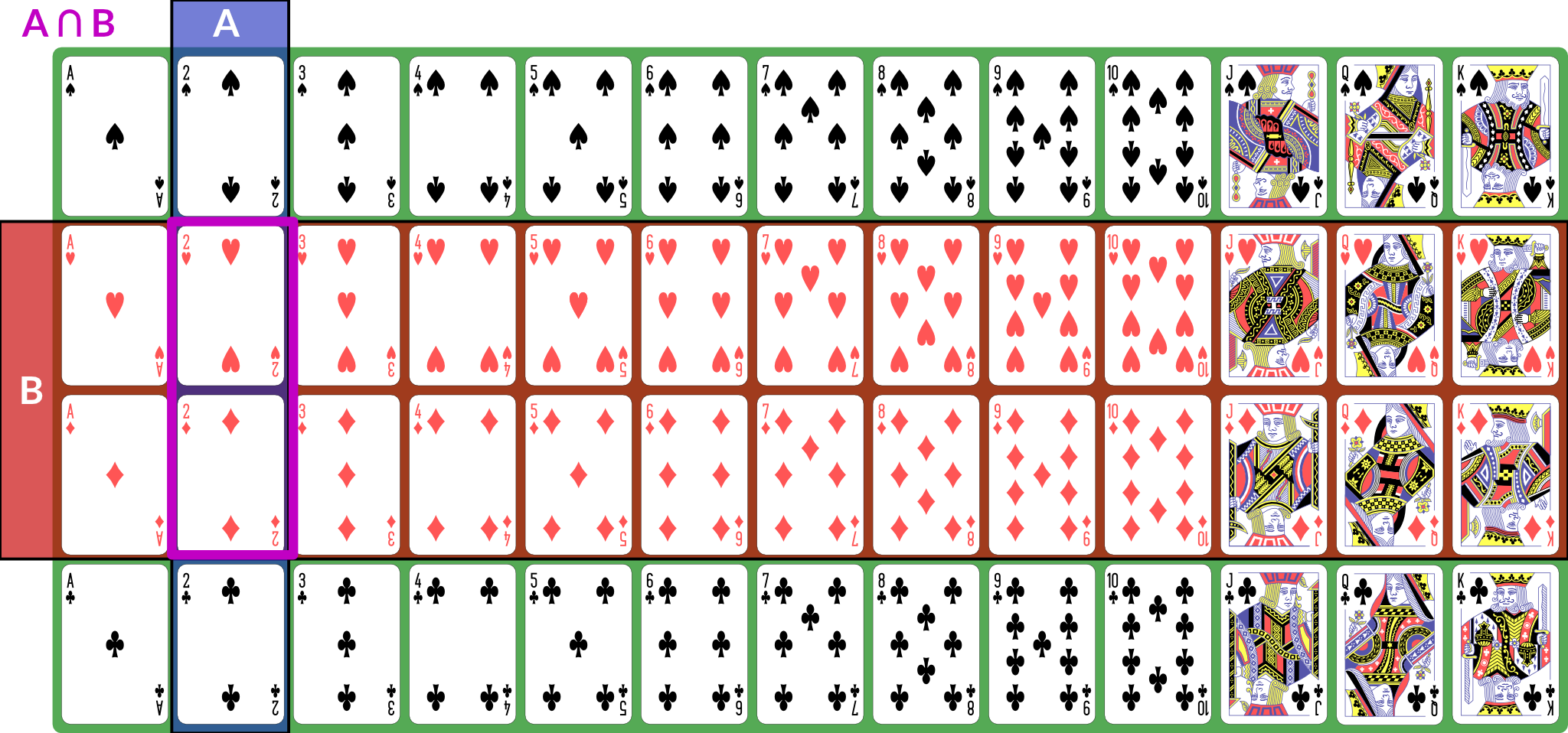

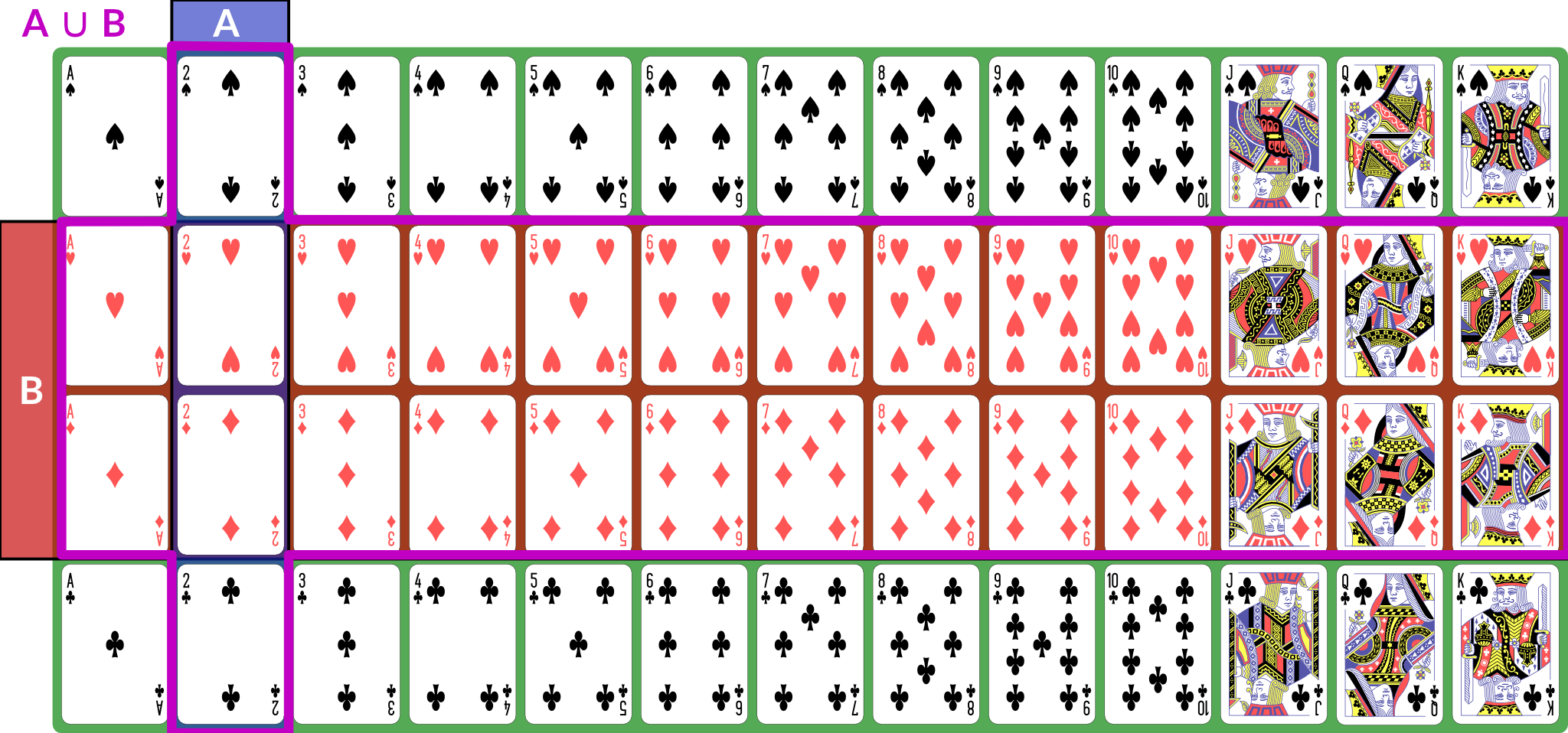

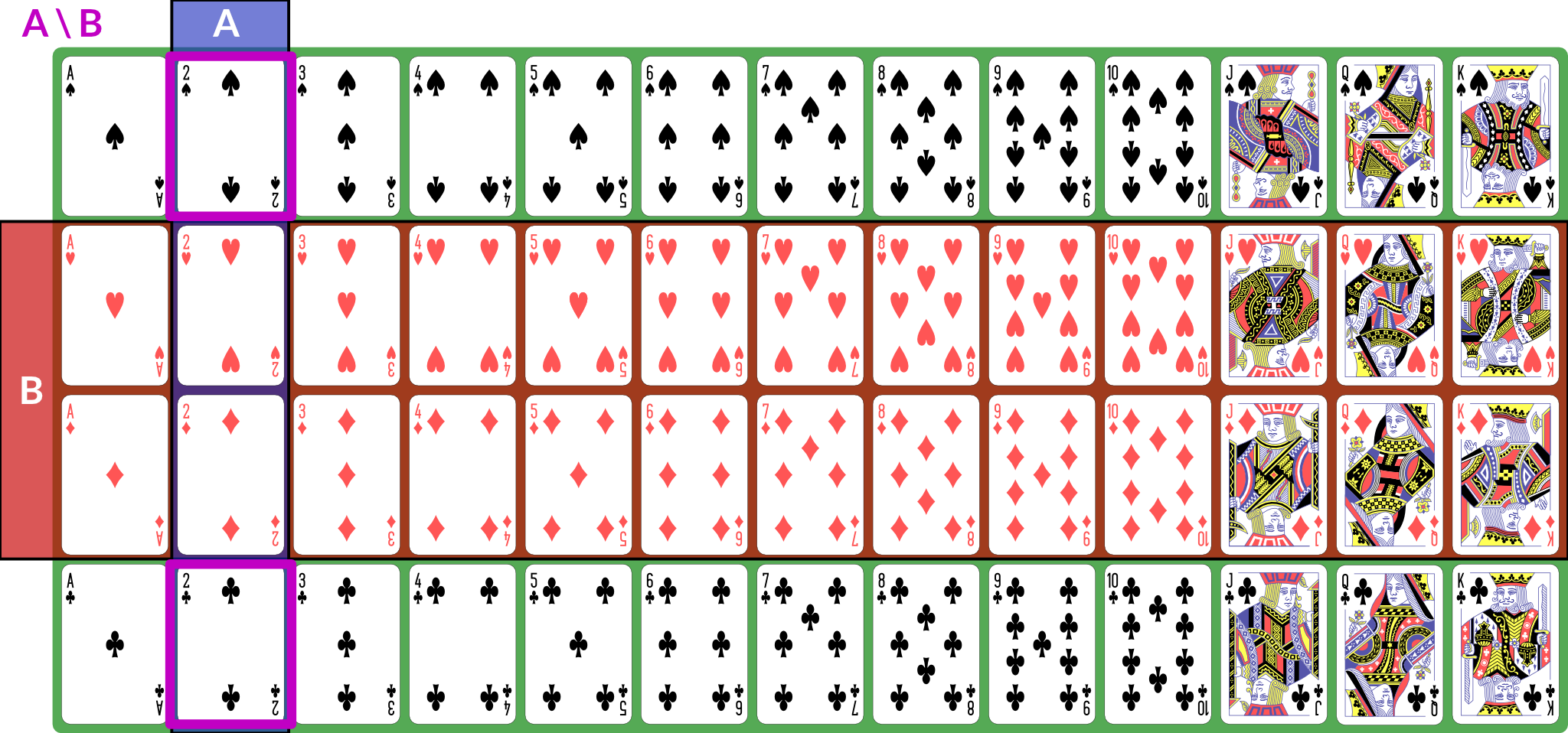

We use set operations to combine events (for these examples, we consider

Illustration

Illustration of

Illustration of

Illustration of

With these definitions, we can now define the event space:

If

Since

If

Here are some additional properties of sigma algebras (these are listed separately from the previous properties because those are the definition of a sigma algebra and these are consequences — we can prove them from the definitions and axioms):

If

Probability#

Now that we have a sigma algebra, we can define the concept of probability.

A probability distribution (or measure)

If

A collection of disjoint sets is also called mutually exclusive. What it means is that for any

We a field of events equipped with a probability measure

What this probability measure does is that it describes how

“much” of the total probability is associated with event. This is sometimes

called the probability mass, because probability acts like a conserved

quantity (like mass or energy in physics). There is a total probability of 1

(from the first axiom

Interpreted as a description of long-run frequencies, if we repeated the random process infinitely many times, half of the times should be

Interpreted as an expectation of future observations of currently-unobserved outcomes,

The non-negativity axiom keeps us from trying to assign negative probabilities to events because they won’t be meaningful, and the countable additivity axiom ensures that probabilities “make sense” in a way consistent with describing a distribution of mass across the various events. If we have two distinct, disjoint events, then the probability mass assigned to the pair is the sum of their individual masses; the axiom generalizes this to countable sets of disjoint events.

Aside

There do exist probability frameworks in which negative probability makes sense, but they are unusual and we won’t be needing them.

Some additional facts about probability that can be derived from the above axioms:

If

Warning

We have to be careful with

Joint and Conditional Probability#

We define the joint probability

The conditional probability

Conditional and joint probabilities decompose as follows:

From this we can derive Bayes’ theorem:

We can marginalize a joint distribution by summing. If

We call

Independence#

Two events are independent if knowing the outcome of one tells you nothing about the probability of the other.

The following are true if and only if

Continuous Probability & Random Variables#

If

Instead, we define a sigma field where events are intervals:

This is not the only way to define probabilities over continuous event spaces, but it is the common way of defining probabilities over real values.

This particular sigma-field is called the Borel sigma algebra, and we will denote it

We often talk about continuous distributions as the distribution of a random variable

We define continuous probabilities in terms of a distribution function

This is also called the cumulative distribution function (CDF).

We can use it to compute the probability for any interval:

This probability is called the probability mass on a particular interval.

Distributions are often defined by a probability density function

Unlike probabilities or probability mass, densities can exceed 1.

When you use sns.distplot and it shows the kernel density estimator (KDE), it is showing you an estimate of the density.

That is why the

We can also talk about joint and conditional continuous probabilities and densities. When marginalizing a continuous probability density, we replace the sum with an integral:

Note

Technically, a random variable for a probability space

Expectation#

The expected value of a random variable

If

Note

If we use the technical definition of a random variable, then we denote:

We can also talk about the conditional expectation

Variance and Covariance#

The variance of a random variable

The standard deviation is the square root of variance (

The covariance of two random variables is the expected value of the product of their deviations from mean:

The correlation

We can also show that

Random variables can also be described as independent in the same way as events: knowing one tells you nothing about the other.

If two random variables are independent then their covariance

Properties of Expected Values#

Expected value obeys a number of useful properties (

Linearity of expectation:

If

If

If

Expectation of Indicator Functions#

Sets can be described as an indicator function (or characteristic function)

Then the expected value of this function is the same as the probability of

Odds#

Another way of computing probability is to compute with odds: the ratio of probabilities for or against an event. This is given by:

The log odds are often computationally convenient, and are the basis of logistic regression:

The logit function converts probabilities to log-odds.

We can also compute an odds ratio of two outcomes:

Interpretation#

So far, this document has focused on probability as a mathematical object: we have a probability space obeying a set of axioms, and we can do various things with it. We have not, however, discussed what a probability is. Is it a description of frequencies? Something else?

Under the instrumentalist school of thought, the mathematical definition above is what a probability is. Probability is a measure over a sigma algebra that satisfies Kolmogorov’s axioms, nothing more, nothing less. In this view, all other interpretations of probability are simply applications of probability.

Frequentism defines probability as the long-run behavior of infinite

sequences: the probability of an event is the fraction of times it would appear

if we repeated the experiment or observation infinitely many independent times.

Subjectivism or subjective Bayesianism defines probability as a

consistent description of the beliefs of a rational agent. That is, it

describes what the agent currently believes about as-yet-unobserved outcomes.

There are variants on these theories and other theories as well. They may seem similar, but they are very different in terms of their implications and application. For one thing, under frequentism, probabilities only make sense in the context of repeated (or theoretically repeatable) random events, and we cannot talk about the probability of a fixed but unknown thing, such as a population parameter. Under subjective Bayesianism, because probability is about the agent’s subjective state of belief, we can talk about the probability of a population parameter, because all we are doing is describing the agent’s belief about the parameter’s value.

Note

When I use the term subjective above, I am not using it in a perjorative or negative sense. I am using it in its philosophical sense: it is the agent’s internal state, which is not necessarily shared with other agents. Different rational agents may have different current beliefs, each entirely rational and well-justified, because they have access to different prior information. There is nothing positive or negative about this; it is just a fact.

Further Reading#

This thread by Michael Betancourt provides a good overview of the instrumentalist idea of probability, which treats probabilities simply as their mathematical objects. It influenced how I write about mass above.

If you want to dive more deeply into probability theory, Michael Betancourt’s case studies are rather mathematically dense but quite good:

Product Placement (probability over product spaces)

For a book:

Introduction to Probability for Data Science by Stanley H. Chan

Introduction to Probability by Grinstead and Snell

An Introduction to Probability and Simulation — a hands-on online book using Python simulations

A Probability Path by Sidney Resnick